In post-war Lodz, returning Jews settled in urban centers due to economic prospects and a sense of safety that was no longer felt living in small towns. Anti-Semitism was quite prevalent in Postwar Poland. Despite the attempt of mass eradication of Jews throughout Europe, there was hardly any empathy or compassion towards Jews in Poland. Jews were still often perceived as a threat. Anti-Semitism in Poland after the war ranged from derogatory comments and escalated to assaults, murders, and pogroms.

Anti-Semitic pogroms popped up in several cities in Poland after the war. Jews were taken from train stations and killed in mass numbers. Based on official reports between 1944-1946 more than 300 Jews were killed. Unofficial numbers, however, range from 400 to 1,500. Only 9 jews were killed in Lodz during this time period. The killings decreased towards the end of 1946.

Many of those who survived the war wished to return to their homes and found Poles living in them. Some tried to seek legal action to reclaim their property yet, these attempts were often unsuccessful.

Population

By July 1945, more than 20,000 Jews settled in Lodz. The population was at a steady increase during the post-war life. By the end of the year, the population had increased to 30,000. At this time Lodz made up 40% of the Jewish population in Poland.

But what was it about Lodz that made the pre-war population want to return to Lodz? Due to the ghetto being situated outside of the actual city of Lodz, a majority of the city was still intact and many of the returning Jews wished to return to their former residences.

Due to the orders to have children under 10, the elderly, and sick sent to their death the post-war population was constituted 85% of people between the ages of 15-45. Only 3% of this population was children, under 7.4% of the population was aged 7-5. Adults over 45 made up 8% of the post-war population.

Despite the difficulty of readjusting to post-war life, babies were still being born to Jewish families. In only one year, there were 500 Jewish babies born. In 1947, a Jewish hospital was opened to accommodate the growing baby boom.

Because of the disparity in the age range by mid-1945, less than 1,000 children lived in Lodz. By the beginning of 1946, the number of children living in Lodz rose to over 2,000. The population steadily increased to 4,500 by the end of the year.

Education

The first Yiddish and Hebrew schools were established as early as 1945. It was thought to have 45 students. A major problem with the education system after the war was most children who survived did not speak Hebrew rather Polish. The constant ebb and flow of teachers and students in the years after liberation made it harder to create a stable school environment and lacked a sense of normalcy.

The Hebrew school severed as a private educational institute and was the first Hebrew school in post-war Poland.

In 1946, the Yiddish school’s enrollment almost tripled to 180 students. This number would increase again by the end of the year with numbers doubling to 400.

Jobs

Over 100 Jewish cooperatives were set up to support returning Jews after the war. The cooperatives provided jobs such as shoemaking, carpentry, and metalworking. As early as 1946, the cooperatives employed more than 2,000 Jews in Lodz.

Trials held in Lodz

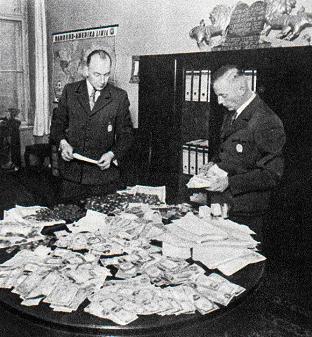

Post-war Lodz held two trials against Nazi perpetrators: Hans Biebow and his right-hand officer, Rudolf Krampf.

Hans Biebow, also known as The Butcher of Lodz, was the Nazi liaison for the Lodz ghetto.

Fig. 38.

Biebow’s cruel behavior led to starvation and death within the ghetto. Although his official duties were to implement Nazi policies in the ghetto, he was personally involved in the torture, rape, and killing of Jews living in the ghetto. He used his position to take ahold of Jewish properties and valuables.

Biebow had been traveling when the Red Army came in and liberated the ghetto in January 1945. Biebow was captured and sent back to Lodz where he was to face trial for his crimes during the war.

Biebow’s trial was held from April 23 to April 30, 1947. He was executed by hanging on June 23, 1947.

Fig. 40.

These two trials were held in Lodz after the war to hold the two Nazi perpetrators responsible for their crimes during the war. From the statics listed above Lodz’s Jewish population had no issues bouncing back after the war. The crimes of the Nazis did not hold back the Jewish people.

Lodz Ghetto Memorial (Radegast Station)

The Monumentum Iudaicum Lodzense Foundation is an organization that helps preserve the Jewish heritage in Lodz. In 2002, they proposed the preservation and creation of the Lodz ghetto memorial. In 2005, the memorial was opened to the public.

The Lodz memorial consists of the Radegast Station and other commemorative features.

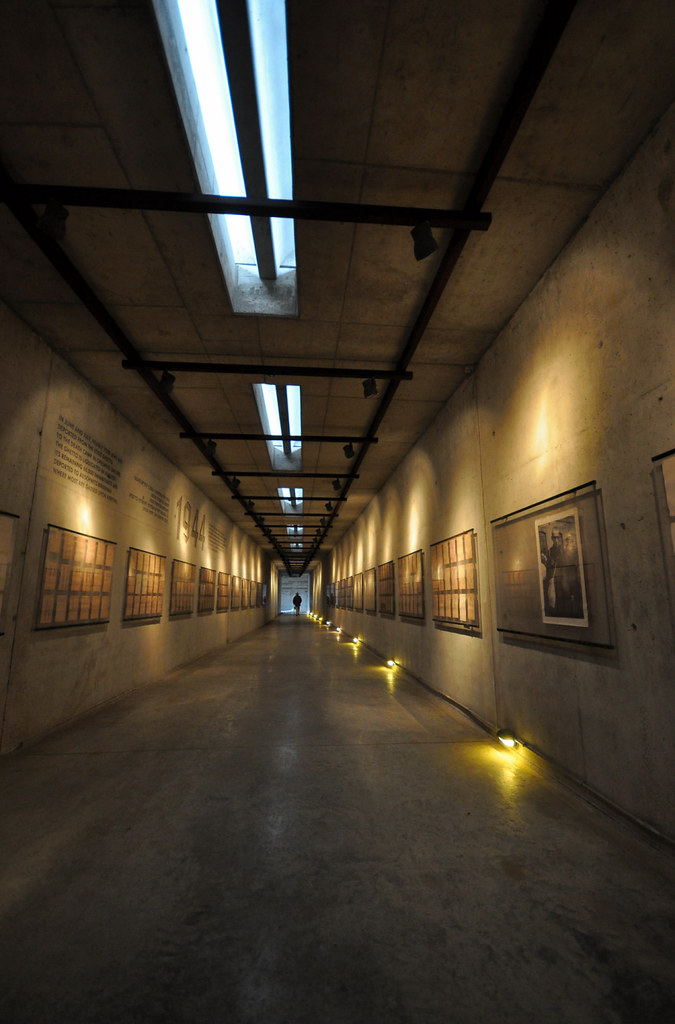

Fig. 43.

The Radegast station was the station in which the Lodz ghetto inhabitants were transported in and out of the ghetto. The station was also the site where raw materials were transported in, and finished products that were produced in the ghetto factories were transported out to support Germany and the war effort. Outside of the station sits an original German train with 3 railroad cars.

The memorial is also made up of a chimney shaped monument with the inscription, “Thou Shall not Kill.”

Fig. 44.

Here is pictured an over 450-foot-long “tunnel of deportees,” which lists the names and photos of those who were deported.

Fig. 45.

The Lodz Ghetto Memorial’s contribution to the collective memory of Jewish identity is shown through the 6 tombstones. The tombstones connect those persecuted throughout Nazi-occupied Europe in this space and place. For example, both the Jews of Rome and the Lodz Ghetto were deported to Auschwitz. The experience at Auschwitz intertwines the current Jewish quarter in Rome and Lodz ghetto’s collective memories. Holocaust memory connects these two spaces and enhances collective Jewish identity. Death camps are deeply spatial and collective memory triggers as they tie together many narratives from the Holocaust. The death camps play into the collective understanding of the final fates of many victims of the Holocaust. The death camp experience also connects the two locations through a shared spatial connection as well. The memories that are shared between the two locations are connected through their Holocaust memory. Thus, this connection strengthens and validates shared collective memory of Jewish diasporic experience.

These 6 tombstone markers have the names of concentration camps. They are engraved with outstretched hands reaching towards the sky.

Fig. 46.

A goal of this project was to invoke emotion and understanding of what happened in the Lodz ghetto. I find this particular video does a good job of relaying the magnitude of severity that this memorial represents.

The Lodz memorial does not speak to the current life of Jews in Lodz rather the memorial serves as a reminder to the millions of lives that were lost during World War II. Its space is suspended in time and serves as a gateway to the past. The memorial’s spatial association to the past plays a large role in the collective memory of Jews and is reflective of other’s experiences. Sites of atrocities hold collective memory and identity. Memorials that are built on sites of atrocities go beyond the goal of perseveration but are historical sites.

Although the Lodz ghetto memorial seems fixed to one narrative the site holds an emotional response and transnational connection to racial and religious crimes. The crimes of the Holocaust lead to the term “Crimes Against Humanity”, which is now used to describe the genocidal crimes committed by political or social systems. Those who are non-Jewish may relate to this site as it has the potential to resonate with a similar historical event within their own society.

Works Cited

Redlich, Shimon. “Jews In Postwar Lodz.” Life in Transit: Jews in Postwar Lodz, 1945-1950. Academic Studies Press, Brighton, MA, 2010, pp. 53–86. JSTOR www.JSTOR.org/stable/j.ctt1zxshxk.18