In 1870, under the leadership of King Victor Emmanuel, the new Italian kingdom nullified previous laws such as Jews living in the ghetto. Italy was now one unified kingdom and sought to build a new inclusive identity. Although Jews were no longer forced to live in the ghetto, the ghetto was not officially closed until 1885.

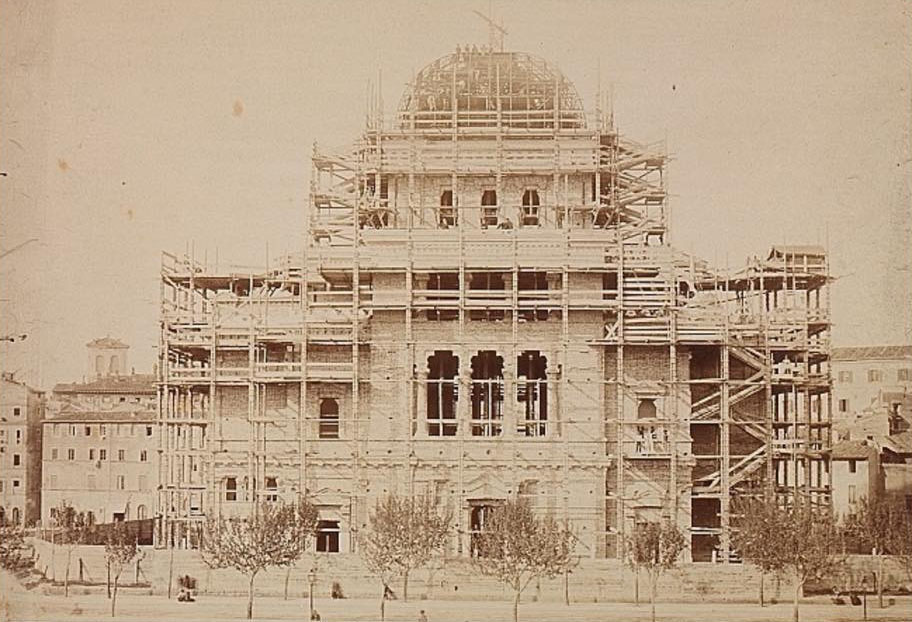

In the wake of the unification of Italy in 1870, the Risorgimento was an attempt to remove the history of the ghetto as a stain on the new identity of Italy. With Rome now as the capital of Italy, the Risorgimento sought to erase “a source of epidemics and a disgrace to the capital.” One of the public works that came out of the Risorgimento was the construction of The Great Synagogue of Rome, which opened in 1904. This was an attempt to give Rome a new appearance through the revamping of undesirable areas, starting with the ghetto.

The term risanameto, was attributed to the remodeling of the ghetto. Sano, meaning to return to health, was a slogan for the ghetto as it moved from its former function into the role of a cultural and religious center for the Jews of Rome. Thus, the synagogue was intended to mask the atrocities of the former ghetto, while also signifying the emancipation and inclusion of Jews as Italian citizens.

Many of the original structures of the ghetto were demolished and a platform was built to create higher elevation to avoid flooding from the river. The synagogue was built in its ruins and some of the ghetto’s architecture is still visible in the basement of the synagogue which houses a museum dedicated to the centuries of Jewish history.

The Great Synagogue can be thought of as a living space. Living spaces are often included within the community’s daily life. Commemorative sites serve not only for remembering but can provide different functions in allowing these locations to become a part of daily life.

Symbolism

The Great Synagogue is imbued with symbolism. Christian architects, Osvaldo Armanni and Vincenzo Costa were the designers of this eclectic synagogue. Its Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Islamic styles are symbolic of the different historic locations and influences on the Jewish community. The combination of the different styles shows the inclusion of different communities despite the diasporic experience Jews have faced throughout history.

The squared and the colored aluminum dome is one of the most unique in Rome. The dome was designed in a square fashion in order to stand out against the traditional round shape of churches. The dome can also be seen from any vantage point in Rome. The symbol of the rainbow first appeared in the story of Noah’s Ark. After the flood, God promised he would never send another flood to wipe the earth. The symbol of his promise was a rainbow. The rainbow inside the synagogue is symbolic of better times to come for the Jewish community.

The inside of the synagogue is reflective of a church, as the architects were Christians and incorporated elements they were familiar with. Synagogues bimah or pulpit, are usually located in the center of the synagogue. However, there is an alter style platform at the front of the synagogue and a rounded niche area which is also similar to a tabernacle area of a church. Although the non-central pulpit can be found in many synagogues, this particular cathedral design is indicative of the designer’s style. Note there is still a women’s section in the balcony portion of the synagogue. This was and still is a common element of synagogues throughout the world.

The Ten Commandments with the menorah on top of the synagogue are common imagery at any synagogue, however, the sunbeams behind the tablet symbolize the new life and prosperity which the Jewish community was entering into. The synagogue itself is symbolic of the emancipation of the Jewish community in Rome. The tablets and menorah also mark this space as Jewish, as to not confuse it with the numerous churches in Rome.

Another element of this synagogue that makes it so unique, is the Sephardic synagogue in the basement. This section was added in 1932. It was later decorated in 1948 with the artifacts from the original ghetto synagogues. In a similar fashion, this synagogue has a women’s section as well.

After the Expulsion from Spain and its territories in 1492, there was an influx of Sephardic practicing Jews in Italy. During the operation of the ghetto, there were 5 small separate synagogues for the different communities within the ghetto; Roman, Lazian, Sicilian, Catalan, and Castilian.

The Sephardic synagogue is symbolic of the inclusion and importance of the Sephardic experience in the larger story of Jewish Diaspora. This community fled from persecution in Spain and other territories to face further persecution in Italy. The Great Synagogue of Rome stands as a testament to the transformative nature locations can have. Thus, the city of Rome and the Jewish quarter are integral to collective and spatial memory and identity of the Jewish community.

The Jewish Museum of Rome

The Jewish Museum of Rome was established in 1960 but was only a small section in the main area of the Great Synagogue. The museum is dedicated to the centuries of Jewish life in Rome. The museum moved to the basement and was officially opened on November 22, 2005.

Collective memory is a part of all social structures while being produced or denied by social systems through the institutionalization of memory objects such as the Great Synagogue of Rome and the Lodz memorial. Memory objects are items that can evoke memories of the culture, community, or ideals of a specific place or group of people.

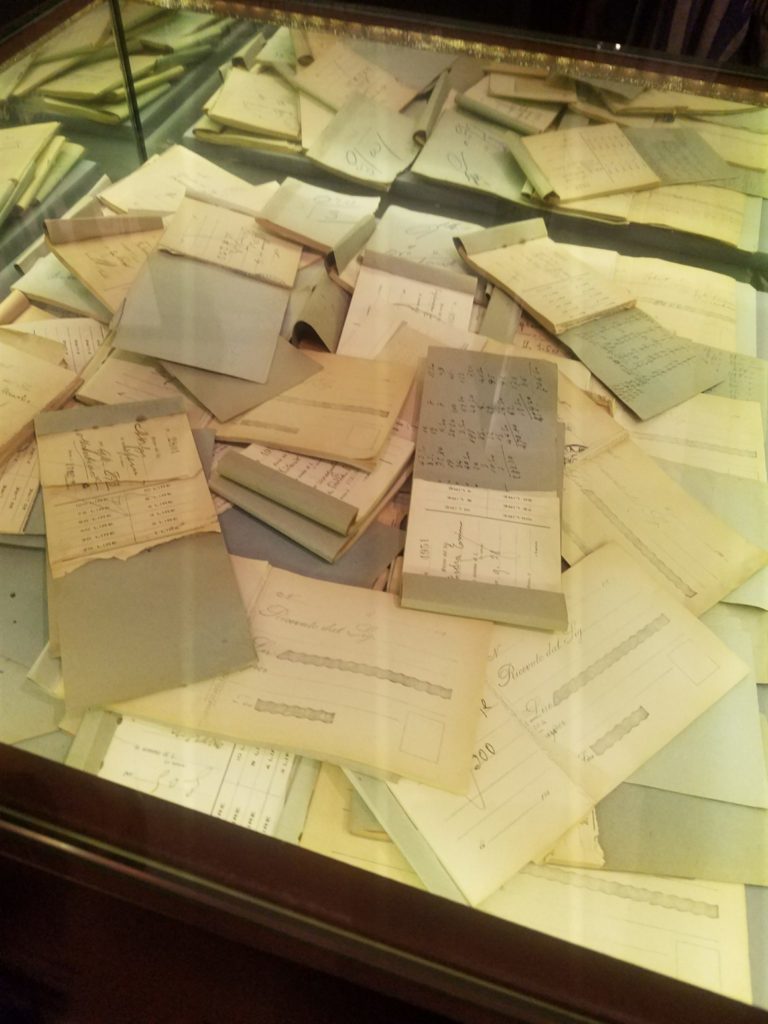

Below are some photos I took while touring the museum. The objects that have been chosen reflect the blending together of communities that live within Judaism. These objects are examined and analyzed to help produce collective and spatial memories, of both the Roman experience but also of the experiences of Jews outside of Rome.

The museum is designed into 7 themed rooms: 1) The wardrobe of textiles; 2) From Judaei to Giudei: Rome and its Jews, from its origins to the establishment of the ghetto; 3) Feasts of the year, feasts of life; 4) The treasures of the Cinque Scole; 5) Life and Synagogues in the Ghetto; 6) From Emancipation to today; 7) Libyan Judaism.

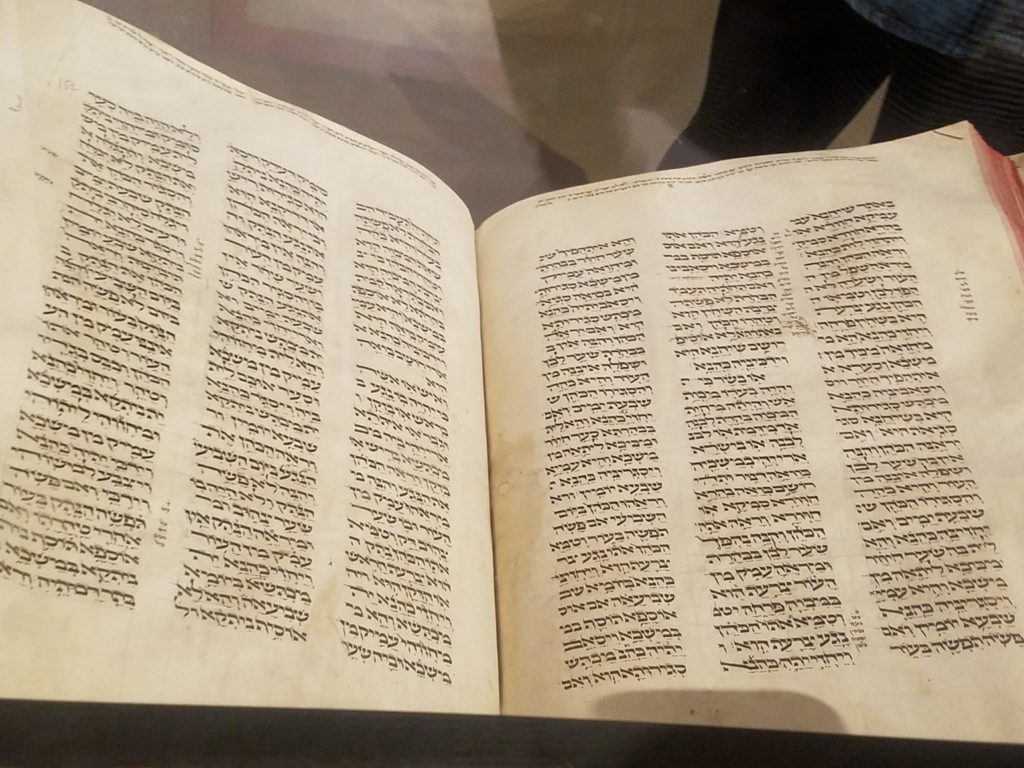

Torah’s and other Holy items cannot be thrown away and are handled with certain measures such as being buried. Torah scrolls are very expensive to make and can only be produced through scribes thus they are handled with extreme reverence.

The Mantel is the decorative and protective covering that goes over the Torah. They are often changed for different Holidays. Also pictured here is the Crown, which adorns every Torah.

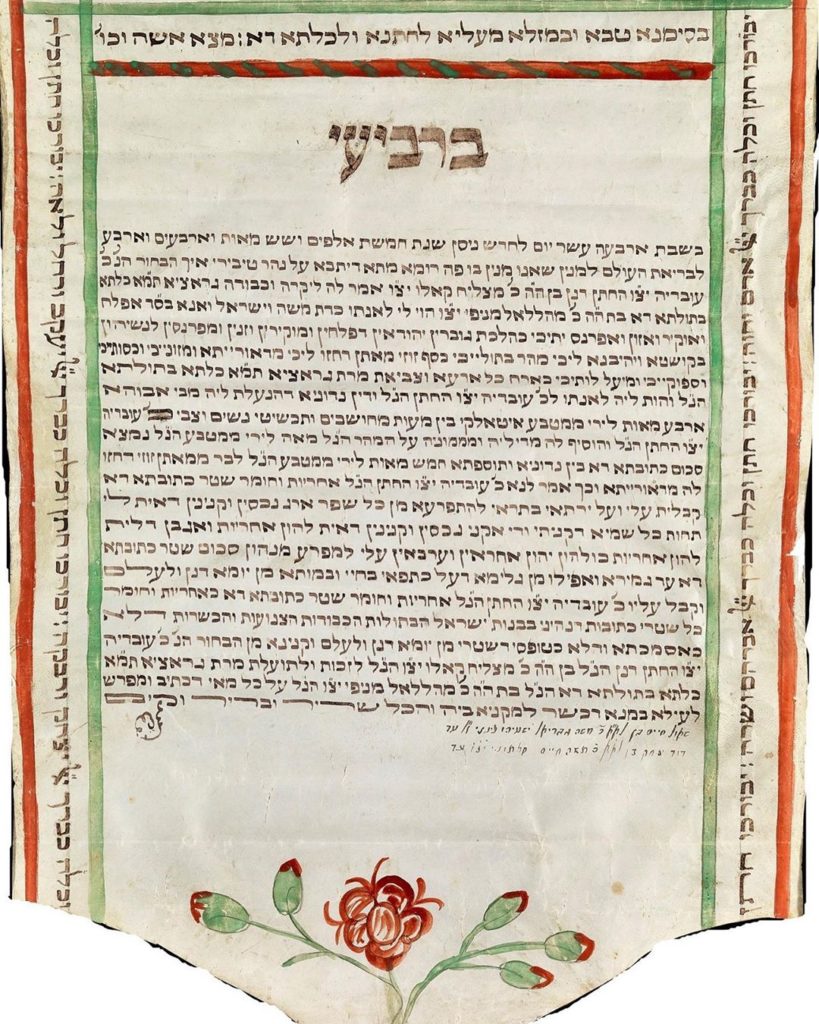

Below is an image of a Ketubah or marriage contract that I saw within the museum. I remember the tour guide pointing out this specific Ketubah, stating this couple was married in 1884, after the unification of Italy in 1870. The couple chose to incorporate the new Italian colors of green, white, and red on their Ketubah to show their Jewish Italian identity. This object is symbolic of the transformative Jewish identity within Rome.

The numerous objects within the museum bridge together the different identities within Judaism. These items build upon the collective identity and experience of the Jewish diaspora through a linear progression of Jewish experience. These objects tell of this experience both within and outside of Rome. The items also depict the transformation of the Jewish community in Rome and the way the former ghetto of Rome has transformed into a cultural center. The quarter now holds positive collective and spatial implications for the Jewish community. The space also allows for remembrance and memorialization of the numerous historical events that have taken place in this quarter over the decades.

Stumbling Through History

During the 1990’s German artist, Gunter Demings created a brass plated cobblestones of persons who died during the Holocaust that displays the name, birth date, the place they were deported to. If possible the year or day they died is also included on the stones. This project is known as Stolpersteine or The Stumbling Stones.

The first stones were placed in Germany as a counter-memorial to Holocaust memory in Germany. Despite being the seat of power for the Nazi party, Germany did not have any death camps. Germany has struggled with its part in World War II and the Holocaust. The project began as a local and individual action and has grown into an international way for others to engage in collective memory practices. The blocks are often placed in front of the person(s) houses that are named on the blocks. If the original location is no longer there, the block is placed in the area of the persons last known location before deportation.

The history of the Holocaust through the Stumbling Stones is communicated in the urban landscape throughout Europe. These blocks are not only for the Jewish community but represent the many other groups who were also persecuted during the war such as Gypsies, Homosexuals, and people with disabilities. This project allows for local and tourist communities to pay attention to and engage in history through daily actives such as walking through the streets.

There are over 70,000 blocks placed throughout 21 European countries, with requests from families asking for blocks in memoriam to their family members. The picture above shows the blocks that can be found in front of the former home of the Sermoneta sister’s, which was located in the Jewish quarter. Rosa and Anita Sermoneta were a part of the over 1,000 Jews rounded up during Nazi occupation of Rome during World War II. It is known that they were deported to Auschwitz and their fates after that is unknown.

Deming’s project localizes collective memory and embeds Holocaust history into the landscape of the city. The stones are placed as an act of remembrance and healing. We become part of history through the process of remembering. This happens by bringing remembrance to the physical space thus manifesting collective memory through spatial means.

Works Cited

Gould, Mary Rachel, and Rachel E. Silverman. “Stumbling upon History: Collective Memory and the Urban Landscape.” GeoJournal, vol. 78, no. 5, 2013, pp. 791–801. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42002548

“Jewish Museum of Rome.” Visit Jewish Italy, 4 Sept. 2019, www.visitjewishitaly.it/en/listing/jewish-museum-of-rome.

Lerner, L. Scott. “Narrating Over the Ghetto of Rome.” Jewish Social Studies, vol. 8, no. 2/3, 2002, pp. 1–38. JSTOR, www.JSTOR .org/stable/4467627.

“Le Sinagoghe.” Sito Ufficiale Del Museo Ebraico Di Roma, museoebraico.roma.it/le-sinagoghe. Accessed 1 Mar. 2020.